Technically, I shouldn’t have been there. I was the only first-level manager in a sea of higher-ups. My fourth-level manager should have attended the weekly meetings. But he was a single 40 year-old, going on 14. The last thing he wanted to do was burn Friday nights at work. I ended up with the short straw.

Technically, I shouldn’t have been there. I was the only first-level manager in a sea of higher-ups. My fourth-level manager should have attended the weekly meetings. But he was a single 40 year-old, going on 14. The last thing he wanted to do was burn Friday nights at work. I ended up with the short straw.

The meetings started at 5:00 pm and ran well past every happy hour in town. Initially I cursed my luck. Ultimately, it changed my management philosophy and how I looked for answers.

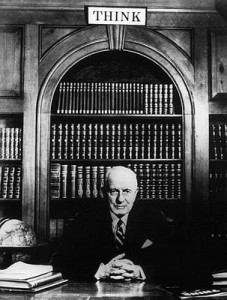

IBM, like many large companies, harbored a culture of hierarchical empty suits and country club WASPs. Maybe that’s why Herb immediately stood out at the Friday night meetings. He was Jewish, had a PhD and was a little unkempt. In an environment of oily political rhetoric, he was candid and blunt. Yet for all his irreverence, IBM entrusted him with its 1500+ semiconductor research and development team the world over.

In IBM-speak, Herb was a “wild duck.” Over the years I came to equate the term with people who didn’t fit IBM’s buttoned-down ideal but who were too smart to ignore. It probably wasn’t a coincidence that a lot of them were also minorities and women.

The thing that most impressed me about Herb was the company he kept. His managers and advisors were smart, motivated and had integrity. But most of all, they openly challenged his decisions – routinely and publicly. And that’s precisely why he chose them.

Most high-level IBM meetings tracked the progress of a predetermined strategy. They were adorned with slick overheads and scripted presentations. During the meetings, everyone politely agreed. After the meetings, a tsunami of whispered dissent wafted down the hallways.

Sleeves were rolled up. Technologies were debated. Presentations were often usurped with hastily scribbled napkin notes. People disagreed, sometimes vehemently. After many hours, the meeting ended. Everyone had their say. People with opposing views sometimes shook hands and slapped each other’s backs, physically acknowledging that dissent was just part of the process. We left tired, changed for the better and in confident lock step.

Friday nights were messy. They were also incredibly inspiring, constructive and productive.

I spent four month’s worth of Friday nights at those meetings. After that, I worked directly for Herb. It took some doing to get that job. I even went so far as to schmooze his girlfriend at the time. But it was worth it.

I’ve worked for a lot of good and bad managers in my day. I worked for only one who was truly great and truly secure. I can still hear him ask: Is this the best solution? Are there alternate opinions and paths we haven’t considered? Can we find someone who disagrees with us?

After a year with Herb, I was asked to head up a project as a middle manager. I surrounded myself with smart, motivated and contentious managers and employees. We pushed each other hard. My boss and my peer middle managers even questioned the tenor of “discourse” that went on in my project.

After a year with Herb, I was asked to head up a project as a middle manager. I surrounded myself with smart, motivated and contentious managers and employees. We pushed each other hard. My boss and my peer middle managers even questioned the tenor of “discourse” that went on in my project.

Interestingly enough, we had one of the highest employee satisfaction rate in our business unit. The area had never produced a patent before our group was formed. Within a year, we had the highest patent-per-employee ratio in the plant.

We started IBM’s first manufacturing consulting business. The idea for the enterprise wasn’t mine. It was a bottom’s up push from employees – not management. The team developed the Washington State Liquor Picker – a computerized order fulfillment system for Washington State’s liquor stores. (My bosses were initially horrified by this project as it involved alcohol) The team also developed the laser optics for Bausch and Lomb’s first laser eye surgery system. And so much more…

I was constantly challenged. It was hard. It was fun. And it became an addiction.

I still have my IBM leather notepad holder, embossed with the word “Think.” I have my personal copy of “Thirty Years of IBM Management Briefings: 1958-1988.” I even have one of the last existing mimeographed copies of the IBM songbook.

But perhaps the most important thing I retained from my IBM days is my love of dissension.

But perhaps the most important thing I retained from my IBM days is my love of dissension.

To this day, I worry when I’m surrounded by people who agree with me. It’s a sure sign that I’m not working hard enough to find better answers.

As an investor, it means I’m listening too much and asking too little. It is a sign that I have to turn off the TV, find new conversations and look harder for dissenting data. It means I have to channel Herb.

Side note: Bob Moffat was one of Herb’s peers back in the day. If Herb was a Wild Duck, Moffat was IBM’s Golden Boy. Bob wasn’t big on dissension; “yes” was more his mantra. Up until last year, Bob was next in line to chair IBM. On June 30th, Bob Moffat will start doing time for charges related to insider trading. Bob may finally learn the benefits of saying “no” the hard way.

Photos: Tom Waston (IBM founder), Often-underused Think desk logo, IBM Poughkeepsie site on a Friday night, Bob Moffat.

One Comment