Today crude oil prices turned lower on speculation that the U.K. and U.S. might coordinate a release from of their strategic oil reserves. If true, it is probably motivated by a desire to shake out speculators. (I wrote about this strategy in a previous post here.) In the short-term, it may even tamp down gasoline prices. Unfortunately, it will do little to stop the well-meaning, but misguided, flow of energy policy rhetoric.

Some people are sure the answer is “Drill Baby Drill.” Others are convinced the answer can be found in conservation. Both camps believe their approach would result in lower gasoline prices in the U.S.

I’ve got some good news and some bad news for y’all.

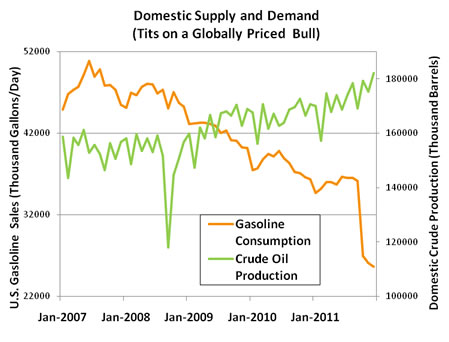

In the last five years, the U.S. has ramped up crude oil production. And whether its because of the flagging economy, higher unemployment, more fuel efficient cars, or the mainstream adoption of GPS (reducing the number of lost drivers unwilling to embarrass themselves by asking for directions) — the consumption of gasoline has dropped dramatically in the U.S.

We’re relatively awash in gasoline. So much so, the U.S. became a net exporter of gasoline in December 2011 — the first time in 50 years. Some analysts believe this trend will continue.

With this double whammy of increased supply and decreased demand, gasoline should practically be free. But of course it’s not. Gasoline prices are running about 8% higher than last year’s already-lofty levels. That’s because gasoline prices aren’t determined by domestic supply and demand. Gasoline prices are, by and large, set in a world market — and the world is worried about tensions in Iran and what that could potentially do to world oil and gasoline supplies.

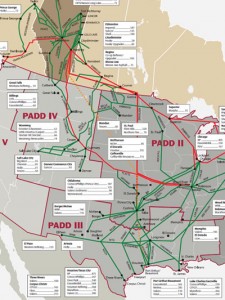

(Pipeline map. Full size image available here)

Have you seen the commercials that portray the Keystone XL pipeline as a magical cure for unemployment and domestic energy supply. It probably would result in jobs. Folks would find some nice short-term work building the pipeline. The Keystone extension could boost refinery jobs on the Gulf Coast. And oil exporters — they’ll get some business — ’cause that Canadian oil isn’t planning on staying here.

There is adequate pipeline capacity to get that gooey tar sands oil from Canada to the U.S. market in Cushing, OK. But that’s not what Canada needs. Over 95% of Canadian crude exports end up in the U.S. market, and Canada wants to diversify its trading portfolio. At least that’s what Canada’s Minster of natural Resources said in this open letter. Canada wants its oil piped to a port (as in export).

Canada isn’t alone. Even the US producers want to escape the glut in the US market. Based on this increased demand to export, Magellan Midstream Partners just announced it would expand its pipeline capacity to the Gulf Coast — moving more West Texas oil to the port.

I’m all for a comprehensive domestic energy policy. We’ve basically been winging it for the last few decades. But its goals have to be grounded on the realities of a world market — not an appealing populist argument built on the fantasy of domestic price setting.

4 Comments