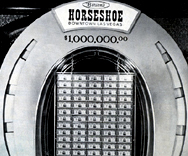

Everyone thought that Becky Binion Behnen had a lock on the worst WSOP legacy. She has served as the casino manager’s equivalent of Herbert Hoover. After an ugly family legal battle, Becky wrested control of Binion’s Horseshoe from her brother Jack and proceeded to milk it dry – even selling off the million dollar display with 100 Salmon P. Chase $10,000 bills. On January 9, 2004, U.S. marshals seized Binion’s cash and shuttered the doors because of Becky’s failure to pay into employee medical and pension plans – which weren’t the only bills she was behind on. Within five and a half years, Becky had reversed the fortune of one of Las Vegas’ most profitable casinos. And perhaps worst of all, she had jeopardized the future of the WSOP.

Everyone thought that Becky Binion Behnen had a lock on the worst WSOP legacy. She has served as the casino manager’s equivalent of Herbert Hoover. After an ugly family legal battle, Becky wrested control of Binion’s Horseshoe from her brother Jack and proceeded to milk it dry – even selling off the million dollar display with 100 Salmon P. Chase $10,000 bills. On January 9, 2004, U.S. marshals seized Binion’s cash and shuttered the doors because of Becky’s failure to pay into employee medical and pension plans – which weren’t the only bills she was behind on. Within five and a half years, Becky had reversed the fortune of one of Las Vegas’ most profitable casinos. And perhaps worst of all, she had jeopardized the future of the WSOP.

In 2003, Chris Moneymaker won the WSOP Championship, fueling the dream that any amateur player could win poker’s crown jewel. The 2004 WSOP stood to draw a record field. University of Nevada, Las Vegas professor Bill Thompson pointed out that the World Series of Poker had grown and prospered in spite of Becky rather than because of her, But with three months before the scheduled start of the 2004 Series, the event’s future was in question.

Harrah’s quickly swooped in and bought the Horseshoe, immediately selling off the property while maintaining the rights to the WSOP. The 2004 Series was held, and as predicted, attracted a record turnout. Some people bristled at Harrah’s corporatization of the event. Juice was pushed to all time highs. Dozens of new events were added, eroding the value of a WSOP bracelet win. Media rights were sold off to the highest bidder. And even final tables were obscured from view — from family and friends — in an effort to squeeze every last buck out of the Series. But the WSOP lived on. Maybe not in a way that pleased most pre-boom pros. But it survived and even grew.

It’s hard to believe that just five years later, the fate of the WSOP, and even Harrah’s itself, is in jeopardy once again. Like Hoover, who now has the opportunity to go down as the second-worst overseer of the economy, Becky may have a new contender for worst WSOP honors. After all, Becky only drove one profitable casino out of business. Leon Black is now driving the largest casino company in the world into the ground.

Black’s company, Apollo Management had a pretty good track record. It first made a name for itself by buying billions of dollars of junk bonds from life insurance company Executive Life for 50 cents on the dollar. It also was able to revive troubled companies like Intelsat and Telemundo. With its past successes and investors looking to capitalize on the golden age of private equity firms, Apollo had no trouble raising capital. But to some extent, Apollo may have become a victim of its own success. Until the mid-2000s, Apollo had a reputation for being a tough and prudent negotiator, paying rock bottom for troubled assets. But its success developed into an embarrassment of riches.

Leon Black was like a successful online poker player, carefully building his bankroll by picking off fish in mid-limit games. He had a streak of good tournament runs, and all of a sudden he had a monster bankroll. He decided the only game he felt like playing was the equivalent of “The Big Game” in Bobby’s Room. But game selection is everything. And sometimes the deck just stops hitting you in the head.

In February 2006, Apollo bought flagging retailer, Linen’s and Things. At the end of 2006, Black made headlines by making two jaw-dropping deals within the span of a week. Instead of picking up troubled companies and beaten down assets, the deals represented thriving businesses at top valuations. Even though the housing market bubble was already long in the tooth and real estate companies were fetching top dollar, Apollo picked up Realogy, the real estate company that owned Coldwell Banker, Century 21, and Sotheby’s International Realty. The buzz relative to Apollo’s real estate deal, however, was dwarfed by the announcement three days later that it had extended a buyout offer to Harrah’s Entertainment. It was the largest leveraged buyout in the industry’s history.

At the time of the offer, casino companies, like real estate companies, were trading for top dollar – for some of the same reasons. Casinos owned a lot of appreciated real estate. Casino company stock prices were up about 250% from their January 2004 levels. While Leon was being hailed as the master of the buyout universe by the financial media, not everyone was seeing the news as positive. Just after the announcement, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch cut Harrah’s to junk status, while Moody’s changed the outlook on Harrah’s debt to negative.

The fifth largest leveraged buyout in history was going to take a lot of debt. Securing a mountain of short-term debt for the deal, it was assumed that Apollo would eventually refinance to long-term debt and sell off a handful of Harrah’s properties to lessen the debt burden. In fact Apollo restructured the company, putting a number of Harrah’s properties and the mother load of the debt under one business entity, which would simplify the process.

But it took almost a year for Apollo to gain regulatory approval for the deal. And by the time the deal closed in January 2008, shit happened.

For one thing, bath accessory retailer Linens and Things refused to turn around. A little more than two years after Apollo’s acquisition, it was being touted as one of the largest leveraged buyout deals to fail. The credit crunch insured that there would be no cheap or easy credit available for Apollo to refinance Harrah’s short-term debt. There was no credit available for other companies to acquire the casino properties Apollo was planning to sell. And by this time, casino valuations had dropped like a stone. Before long, the share prices of most publicly traded casino companies had retreated by more than 50%.

While other casino companies are struggling through the economic downturn, few (other than Las Vegas Sands) are having the life and death battle that Harrah’s now faces. Without its huge debt burden, Harrah’s would have weathered the storm better than most. Profits would have been down, but there still would have been profits.

In the first quarter of 2008, Harrah’s lost $187.8 million, compared to the $185.3 million it had gained in the first quarter of 2007. In those first three months of 2008, they spent $142.6 million in acquisition and merger costs and paid an additional $371.8 million in interest expense, due to the leveraged buyout.

In the second quarter of 2008, Harrah’s lost $97.6 million — hampered by $291.4 million in additional debt expense. It had made $237.5 million in the second quarter of 2007. In the third quarter, Harrah’s losses came in at 129.7 million. Additional debt costs for the quarter were $317.3 million. A year earlier, they had posted a profitable quarter, raking in $244.4 million.

Last month, Apollo was successful in getting some of their individual short-term debt holders to swap out for longer-term debt. To some extent, the debt holders had little choice. Standard and Poor’s had already announced they were planning to lower the debt rating from junk status to default if Apollo didn’t reduce its short-term debt. In the end, however, this represents marginal relief for Harrah’s, saving maybe $10 million per quarter.

Can Apollo and Harrah’s ride it out? Maybe. But their longevity is certainly questionable. While not as dire as when the U.S. marshals stormed into Binion’s, the WSOP’s future is now more tenuous than it deserves to be. Becky wanted to be the master of her father’s legacy – but greed and ignorance almost ended it. Leon Black wanted to be the master of the acquisition universe. Armed with an Ivy League tutelage and a financial pedigree, you had to give him better odds than Becky. But greed and delusions of grandeur are powerful adversaries.

The 2009 WSOP will clearly go off as planned. And the event is profitable and would surely find a buyer should Apollo need or want to sell it off. The rights to the WSOP would certainly fetch more than the towels from the ongoing liquidation sale at Linens and Things.

While the situation is tragic – especially because it was avoidable — I had to laugh when I read that Harrah’s had increased the rake at Caesar’s to $6 a hand. Harrah’s is carrying over $1 billion in extra interest expense each year because of the buyout. Raising the rake is like emptying the ashtrays to make the train go faster. But that’s what companies do when they’re out of fuel. So I guess it’s safe to say that the WSOP will be short of player perks this year. And don’t expect the juice to move any which way but up.

When people testify that “the house always wins.” I will call Leon and Becky as rebuttal witnesses.

6 Comments